What is the cost in human lives of medical breakthroughs? On Thursday, March 25, the 2021 EST/Sloan First Light Festival hosted an invitation-only reading of LAS BORINQUEÑAS, the new play by Nelson Diaz-Marcano. The play derives its title from Borinquén, the aboriginal Taino name for the island of Puerto Rico, and tells two parallel stories: one about the American scientists who in the 1950s made the world-changing discovery that a pill could prevent conception, and the far less heroic story of how the clinical trial for the pill was conducted with the women of Puerto Rico. The playwright tells us more.

(Interview by Rich Kelley)

Take us back to the origin of LAS BORINQUEÑAS. How did it start?

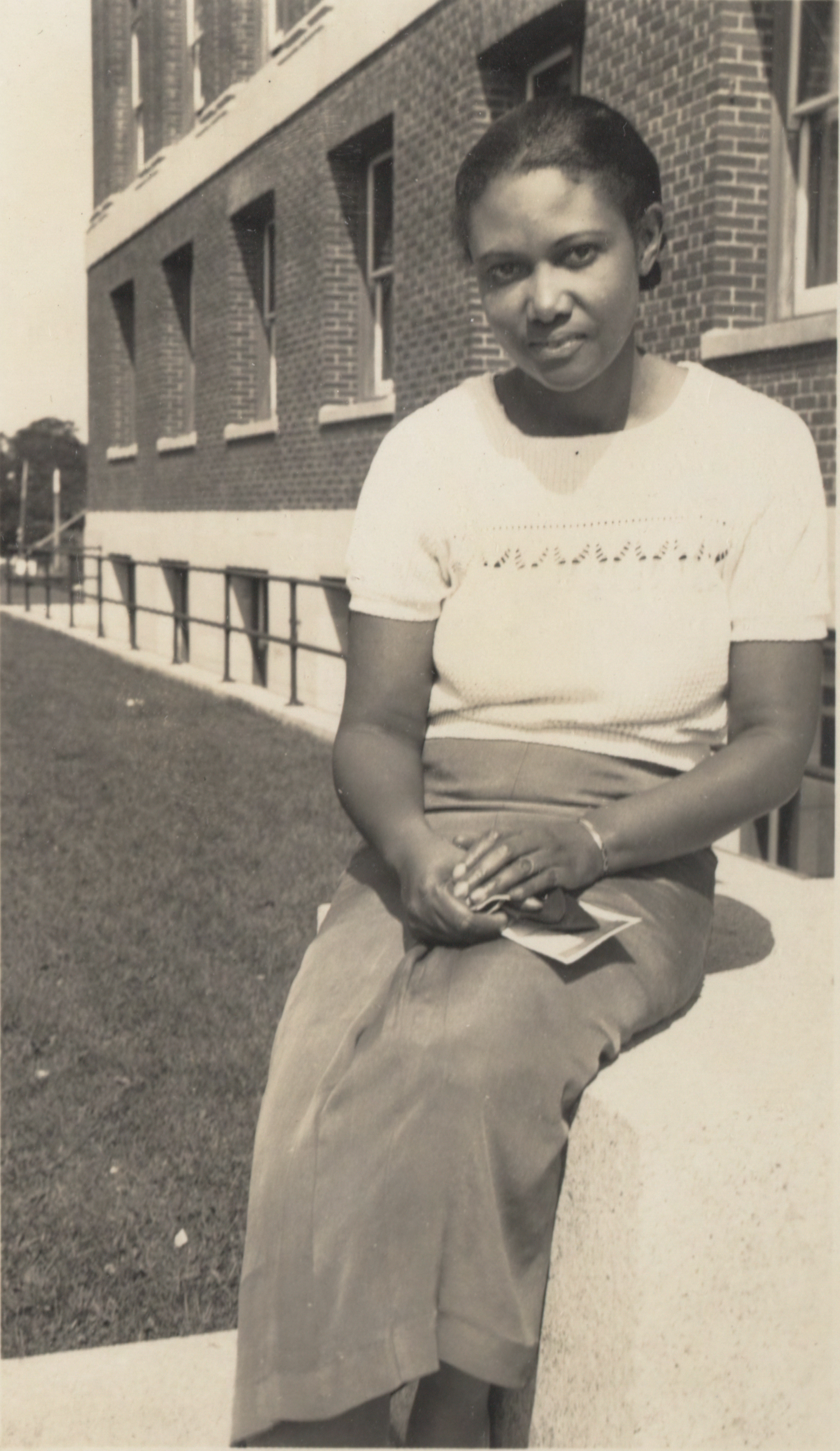

Years ago, as I started doing my research on the Puerto Rican revolt of 1951 for another play, I stumbled upon the details of the birth control mass trials that were conducted in Puerto Rico. While there are plenty of stories about medical negligence and abuse in Puerto Rico, this one fascinated me the most because the results of the experiments ultimately benefited the world. But whose world? Who got the most from these trials? Were the women rewarded for their bodies being used? What was the human cost of the birth control pill? Do good results excuse evil practices? Those questions kept percolating in my mind as I unfolded the history we were never told.

LAS BORINQUEÑAS is part of my life-goal project to expose the hidden/forgotten history of Puerto Rico through the celebration of those who lived it.

What kind of research did you do in writing the play?

I read dozens of academic articles about the trials, about John Rock, Gregory Pincus, Margaret Sanger, Katherine McCormick, the birth control movement and, in particular, the books The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution by Jonathan Eig and A Good Man, Gregory Goodwin Pincus: The Man, His Story, the Birth Control Pill by Leon Sperrof. I watched Ana María García’s 1982 documentary La Operación and spent hours watching stock footage from Puerto Rico and America from that time. And I talked to my grandmother and others who lived during the 50s and 60s to get a sense of how they felt and acted.

Did anything you discovered in your research surprise you?

I want to say yes, but sadly very little surprised me due to the years I spent researching the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. The corruption, the lack of care for the native population, the scientific risks which cost lives — these have all been constant fixtures of that relationship. What surprises me — and always does — is the lives of the survivors after the event. How these women who got no rewards or recognition for their contribution continued raising their kids, taking care of their families, and lived full lives. I am continually surprised by the spirit of the survivors and their complete dedication to live as happily as they can. I wanted to show that in this play.

Several of the characters in the play are based on actual historical figures: Margaret Sanger, Gregory Pincus, John Rock, Edris Rice-Wray. Not everything about them is appealing. How much of these characters reflect what they were like in real life and how much is your invention?

While I took some liberties with their characterization due to this being a narrative work, I didn’t change much of the ideologies they express or the relationships they had with each other.

The clinical trial depicted in the play — testing the contraceptive pill Enovid in Puerto Rico in the 1950s — seems very problematic. What did the participants in this trial know about what they were taking and what effects to expect?

They didn’t know much. Some women thought these pills were part of a survey on family size, others were told these pills were an experimental contraceptive, but they got no specifics about any side effects or the real nature of the experiment. The demand for a contraceptive pill was high at the time, so women flocked to the trial thinking they would be safe. Little did they know the scientists were using them to find out what the actual side effects were and what needed to be tweaked in the formula to make it safe for consumption on the mainland. In other words, to create a better product they were providing pills that they knew could be toxic to these women without informing them of the risks.

Five Puerto Rican women are at the heart of your play; four participate in the trial. How did you decide the right number to have and how to differentiate the characters?

To be honest, there was no specific reason for the number of women. I wanted to create characters based on the women I grew up around in the late 80s and early 90s and their dynamic. While the men were “working,” the women were doing the house chores, trying to take care of the kids. Some of them had jobs, yet all of them were expected to do it all. The best part of their day was when they were able to steal moments for each other. Their conversations always went from religion to politics to whatever happened in the neighborhood that day. They knew everything, had an opinion about it all, but only had each other to decompress with as their men came like storms and changed the environment.

Two characters in the play have a secret extramarital gay relationship. How common was this in Catholic Puerto Rico in the 1950s? Why was this important for you to include?

The thing about queer history is that it’s always been common, we were just not as privy to it as we are today. This is especially true in heavily colonized communities where indoctrination through religion is fierce and brutal. You are not only afraid of the masters, but you are also afraid of the oppressed as they seek to please their masters. There’s always been people hiding in marriages, people being chastised for being too femme/boyish, people being condemned due to their sexuality, for not fitting the mold. I included it in this story because I believe love is the most pure emotion we all share, and even that is decided for them by men.

“Who can they love? How can they love? What are their duties to that love?” These are the questions each woman deals with in this play. The homosexual relationship explores a big aspect of that dilemma.

Why this play? Why now?

These women represent how most of the comforts of this world have been built on the backs of brown and black bodies. This play shows how much of a business the medical industry is and how colonies/poor countries are treated as experimental grounds for the more developed societies. This is very important to know and remember as we go through a pandemic that is killing black and brown people at a higher rate while they demand human rights.

What do you want the audience to take away from LAS BORINQUEÑAS?

I want them to question where their comfort comes from. I want them to understand a bit more about what colonization does to the countries that are supposed to benefit. I want them to realize that many of the things people enjoy in their lives were constructed on top of the lives of people of color. I want them to honor those lives. But more importantly, I want the audience to meet these women and take a little bit of their spirit and culture with them.

Why is LAS BORINQUEÑAS the perfect title for this play?

Because this story is about them, not the trials. It’s about their lives and their dreams. It’s about those women who should be honored every day for their lives. It’s about getting them the recognition they deserve.

The 2021 EST/Sloan First Light Festival ran from February 25 through March 29 and featured readings of nine new plays. Most of the readings were open to the public for free and available on Zoom. The festival is made possible through the alliance between The Ensemble Studio Theatre and The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, now in its twenty-third year.